By Georgina Jerums

Meet RMIT University’s Tim Lutton, named Design Institute of Australia’s Industrial Design Graduate of the Year.

H2 Snow by Tim Lutton - an alpine survival bottle that melts snow into drinking water.

A recycled water washing machine, a survival gadget that turns snow into drinking water, compostable cardboard furniture… Tim Lutton’s a natural for conjuring up a Pandora’s Box of useful designs.

It’s no wonder the 23-year-old Melburnian has been named Design Institute of Australia’s Industrial Design Graduate of The Year (GOTYA) for 2021.

The GOTYAs, launched in 2005, give a showcase to new designers from around Australia.

Unlike other industry awards which celebrate one project, these awards ask graduates to enter three inventions created during their degree.

“Showing a breadth of work was critical,” Tim notes, and his projects – each taking six to 12 months to complete – easily meet that challenge.

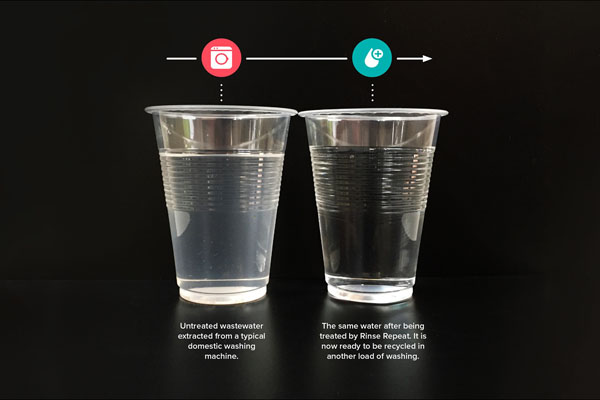

His first submission, Rinse Repeat, allows half of the wastewater produced by front-loading washing machines to be treated then recycled in another load, saving 7800 litres annually. The invention involved analysis of no less than 54 home laundries: now that’s dedication!

His second submission, H2 Snow, is an alpine survival bottle that melts snow into drinking water (removing the need for sun, electricity or gas as heating methods). A handle creates heat through friction, mashing up the snow through a spinning blade. Simultaneously, a copper tube in the bottle radiates heat whilst the blade moves the snow, converting 200g of it into 100mL of water in 20 minutes.

And Tim’s final design submission, C-Pulp, is a bio-material made from waste cardboard and compostable glue used to produce cheap furniture that can be composted at the end of its life cycle.

“I think the reason for the win was that my work always begins with crazy ideas that try to solve real world problems,” says Tim. “When I look at a problem, I love approaching it with questions that flip traditional thinking on its head. I love questions like ‘What’s the most bizarre way to solve this problem?’ My motto when it comes to prototyping is: ‘If you didn’t accidently break something, you weren’t prototyping hard enough’. “

While none of his submissions have made it to market just yet, Tim does have another project called Terrawear (a terrarium domed watch) in the pipeline that “shows promise for future commercialisation”.

Exploring “the intersection between wearable technology and the natural world”, inside the dome is a clump of moss and several small sensors which track the health of the terrarium. The moss requires only a small amount of sunlight and an even smaller amount of water to survive.

In terms of shaping his future, Tim says winning the award has been life changing.

“Studying design at university is an amazing experience but it’s often difficult to benchmark your creative processes against professional design practice. Participating in the GOTYAs has given me the chance to grow as a designer through feedback by industry-leading practitioners. It has filled me with the confidence to keep designing and trusting my instincts.”

And it landed Tim a job. “One of the steps in the GOTYA process was being interviewed by a panel of Australia’s top professional designers. In the days after my interview, I connected with one of my panellists (Chris Ballard of Lex Design Agency, an RMIT Industrial Design alumni) on LinkedIn and was later offered a job at his firm.”

Along with that, Tim has an ever-growing list of “random ideas” to experiment with on weekends, some using a 3D printer. “I don’t feel like slowing down any time soon,” he reflects. “Industrial Design has the ability to catalyse change in a way that brings people hope: in a future that grows increasingly uncertain, hope’s a powerful thing. The sky really is the limit with what you can design. I like to think of industrial design as professional problem solving – what makes it so interesting is industrial designers are trained to think broadly and use skills from several creative disciplines to reach an end goal. We aren’t just one type of designer – we’re shapeshifters who continually adopt new approaches to match the needs of the next problem. It’s this variety that keeps me addicted to the profession.”

Funnily enough, that addiction began in the very oddest of circumstances.

“I was reading a toilet catalogue,” Tim laughs. “In Year 10 I did work experience for a week with an architect. The firm was designing a toilet block for a highway rest stop and asked me to look through a plumbing supplier’s catalogue to pick out which toilets, hand dryers, fixtures etc. that they should use. As soon as I saw this catalogue I was transfixed – I found the products so much more interesting than the actual building they were going into. This led me to ask the architects ‘who designs those products?’ and I was introduced to the world of Industrial Design. From that point onwards, I knew what I wanted to do with my life.”

And advice for budding industrial designers?

“From the daggiest cardboard prototype made in your first week of design school to your final year project, all your work has value,” reckons Tim. “Many people fall into the trap of thinking their work has to be polished and seductive, but this isn’t the case. If your little cardboard model or napkin sketch taught you something valuable, then it’s to be celebrated and proudly displayed in your folio.

“Document everything: there’s no such thing as too many photos, videos or badly-drawn sketches when it comes to developing a design project. Especially document the failures - what doesn’t seem important now may be a critical finding to refer to later. When taking photos of your work, use a white paper background.

Q&A: RMIT industrial design program manager, Dr Juliette Anich

Why are the GOTYAs important for the design world?

They’re different from other industry awards, as unlike others which celebrate one awesome project, these awards ask graduates to show three outstanding works developed over their degree. A graduate needs to show a consistent, high level of work over many years. And we can gather to celebrate exceptional student work across states and national levels.

How’s our state faring in the industrial design space?

Victoria celebrates an incredibly strong design culture and community, and as such we have a very high standard of graduate outcomes. In my opinion, we produce the best design graduates in Australia. Many RMIT Industrial Design graduates go on to win international awards for their graduate work and secure international design jobs, so I think we’re very competitive beyond our shores as well.

How can other design students stand out from the pack?

Be a little bit more curious, work a little bit harder… and love design!

This article was originally published on The Victorian Connection in December 2021.

2021 Finalists

An extraordinary breadth of projects from across the state have been entered in the 2021 program.

View the 2021 FinalistsEntering the Awards

The Awards are free to enter for eligible Victorian designers and architects with submissions across eight design categories.

Learn more about the guidelines and processType on the line above then press the Enter/Return key to submit a new search query