First, we conducted research to understand how pathologists go about their tasks in their offices. We shadowed eight pathologists, observing them diagnose and report cases. We documented their tasks and workflows with a particular focus on:

- How they interacted with objects, including their microscopes, desktops and reference materials

- What information they were using to help diagnose and report, including the notes they wrote or dictated

- What ’work-arounds’ or ’rules of thumb’ they used to make their work more efficient

This helped the team develop a shared understanding of the opportunities to help pathologists.

By collaborating with our colleagues, we helped define a product scope that would not only help pathologists but also be technologically feasible and financially viable for our business.

Second, conceptual mock-ups went through over ten rounds of iteration. Each of these ”design sprints” involved focussing on a specific product question, designing an experiment and concepts to elicit feedback and having at least five pathologists interact with a prototype.

We first delved into questions and decisions that would have the most far-reaching consequences for our product. These included:

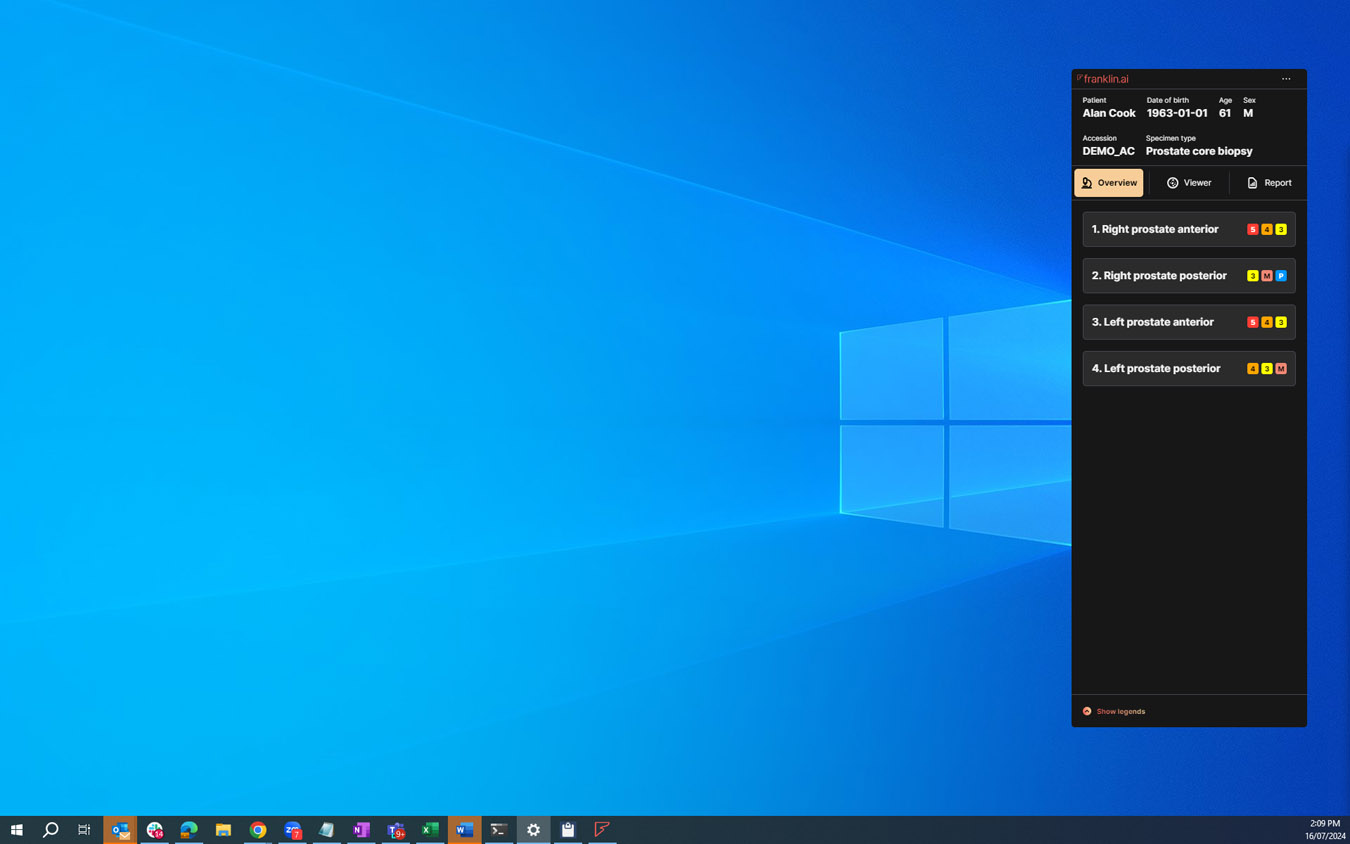

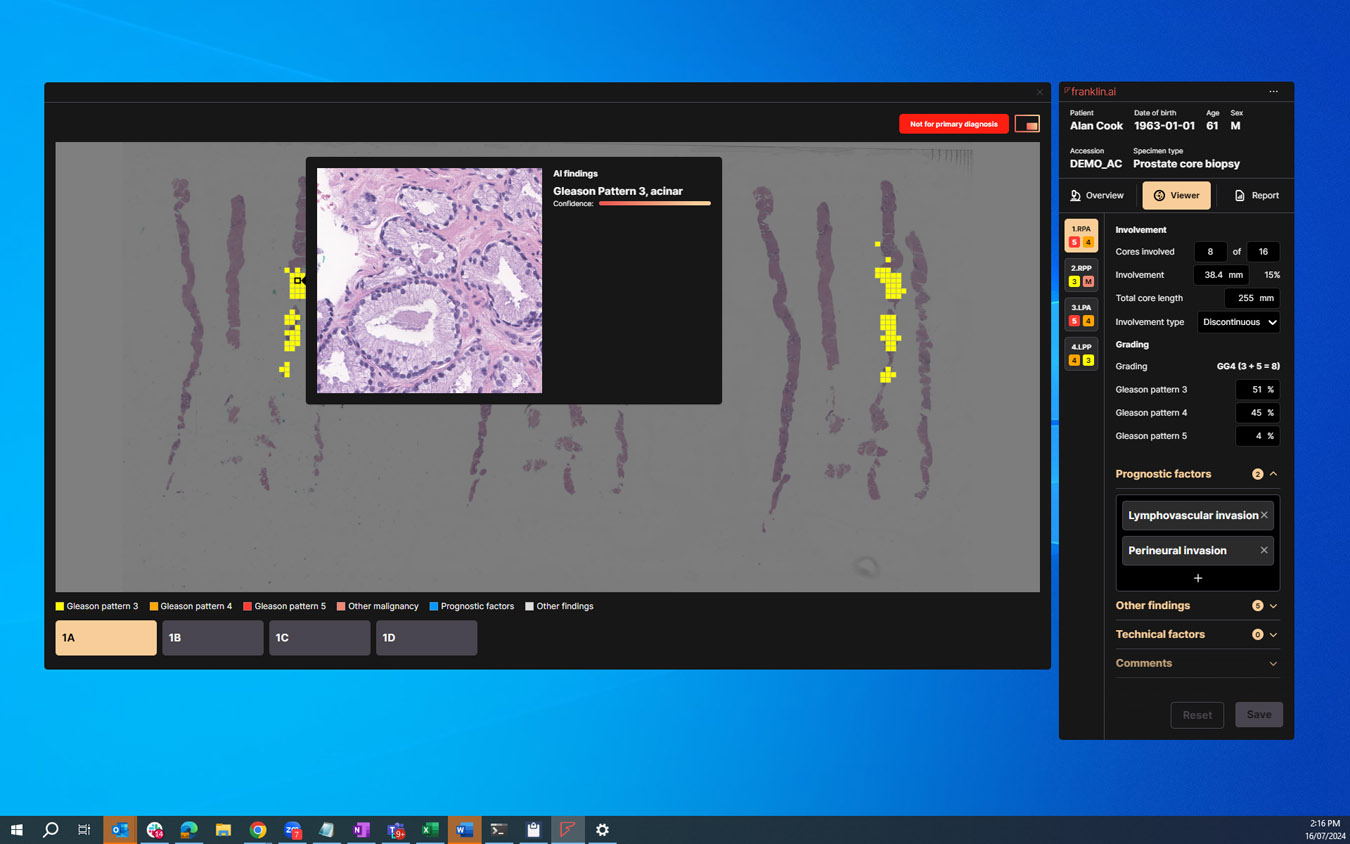

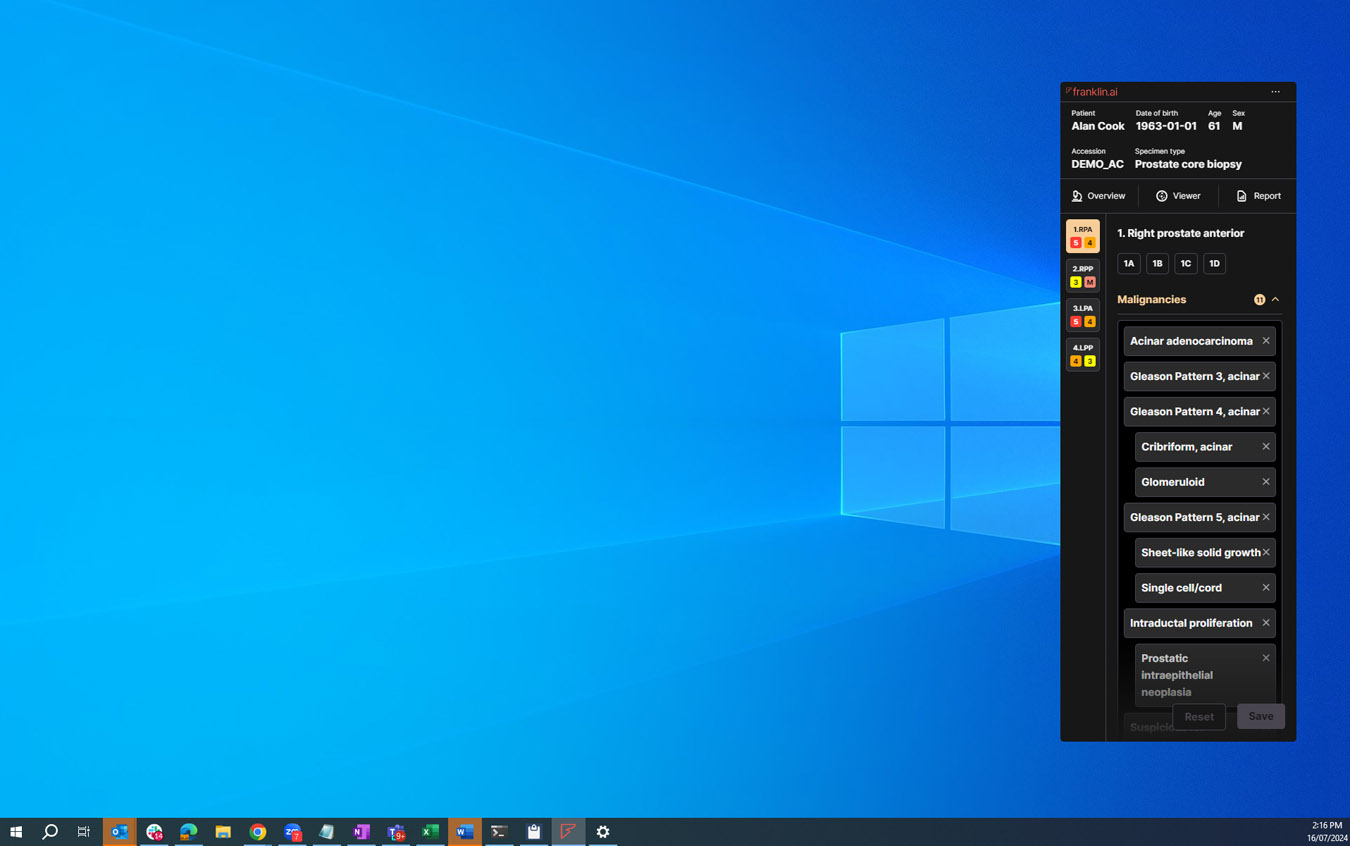

- When and how should the AI findings be presented to the user?

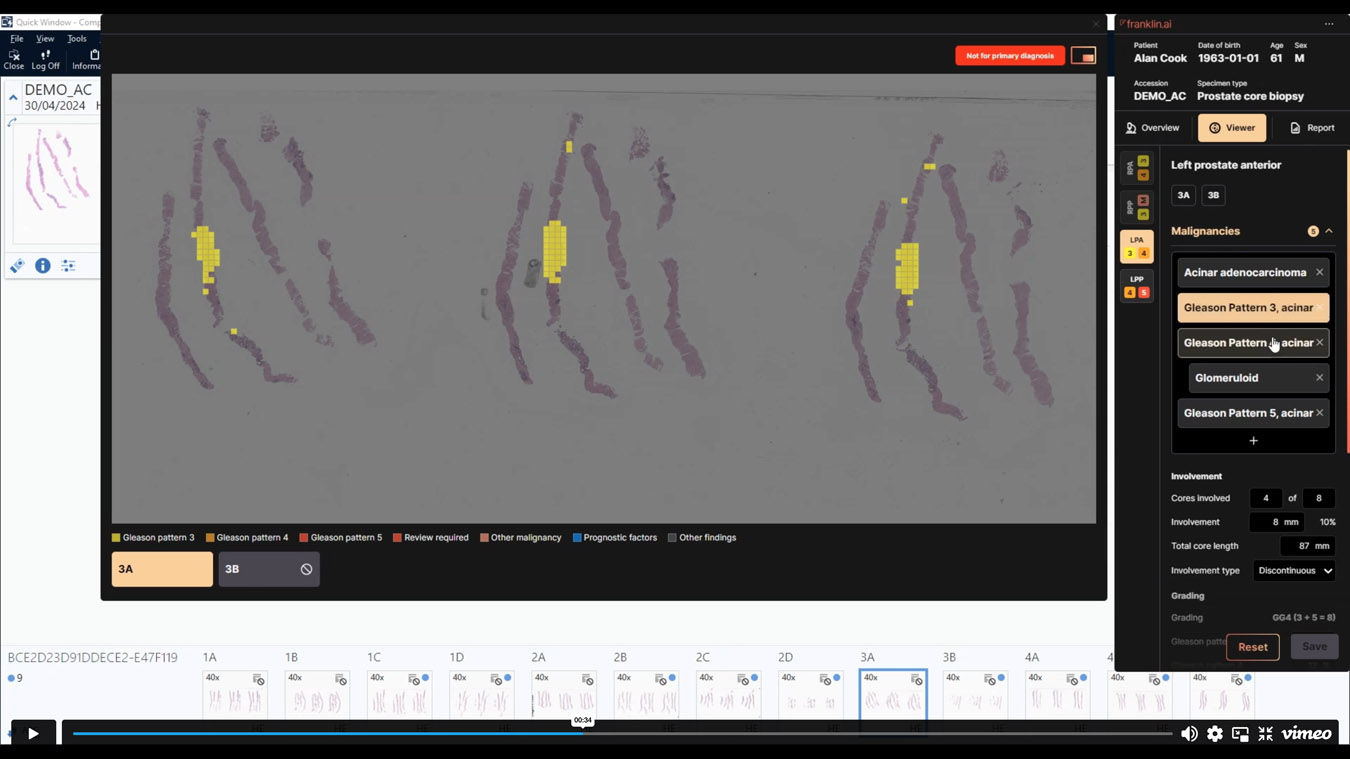

- What was the right ’unit of analysis’ - slides, specimens, or something else?

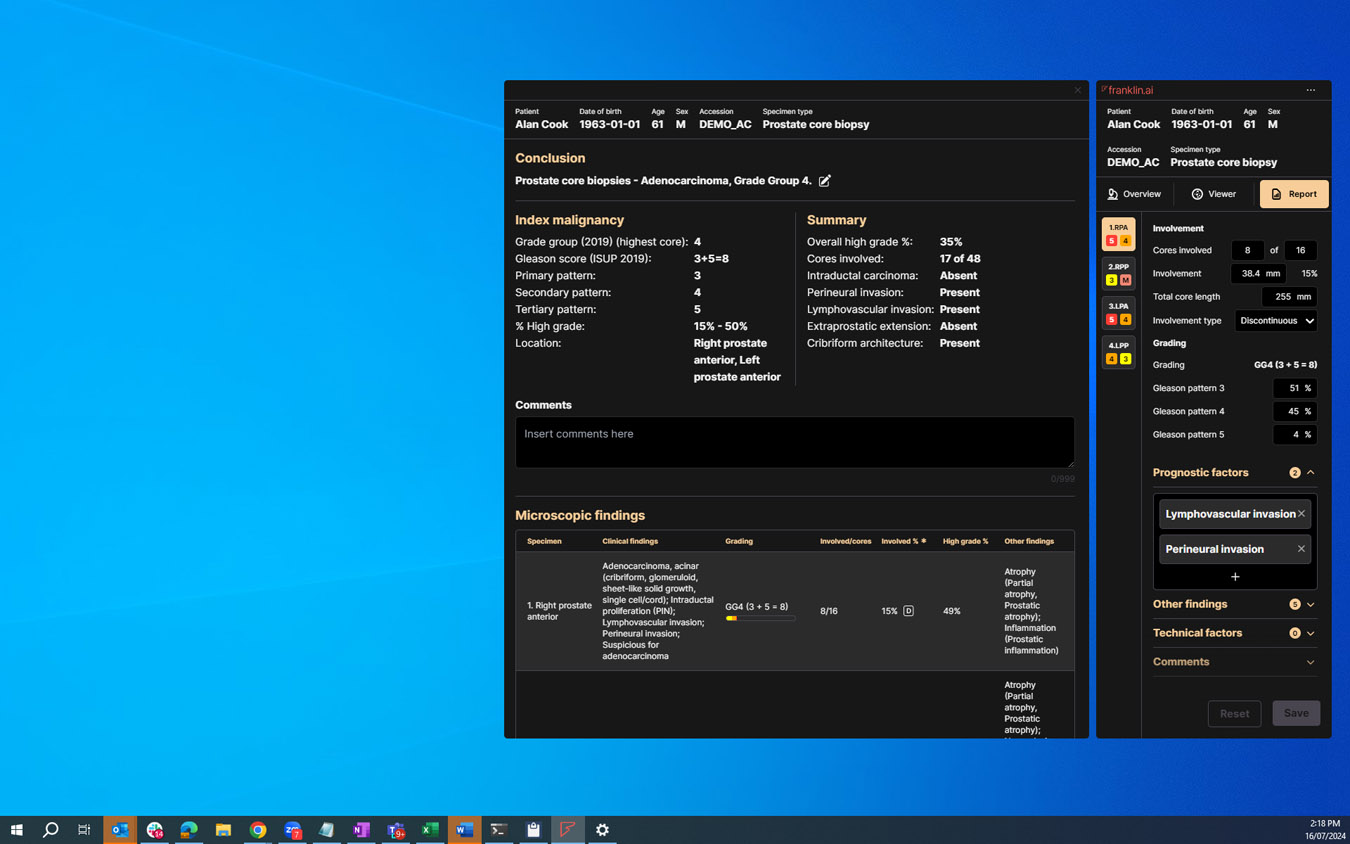

- How should we summarise findings for reporting?

The feedback helped inform workflow, functionality, information architecture and high-level interaction design decisions.

Once these big, consequential decisions were made, we delved more into more nuanced questions such as:

- What should the report look like?

- How should we communicate the probabilistic nature of AI findings?

- How might our product need to adapt to a variety of labs and jurisdictions?

These helped refine our user interface and information design.